This is my second post on Scripture Memory. In my last post on Scripture memory (over a year ago!), I gave you 8 reasons why you should work hard at Scripture Memory. It would be instructive to you to read that post first by clicking here. At the end of that post, there is a video made by my college pastor, Trace Hamiter, explaining how to do Scripture memory through a verse box. What I want to do in this post is not restate what I’ve already said but instead to explain to to you how to build a verse box. This method of Scripture memory has completely change how I think of Scripture memory. It’s no longer intimidating. It makes sense. I have a mission. I have a plan. It’s easy.

So, without further ado, here’s how you get started on a ‘Verse Box’ and begin memorizing the Word of God.

**Note: this method can also be used for catechesis. I have friends who are moms that have found this very helpful in teaching their kids Scripture and catechism.

***Some preacher friends of mine have used separate boxes for illustrations, quotes, etc. I have done so myself.

Supplies for the Box

All of the following can be bought at Target or Wal-Mart (cheaper Bibles and pens, too!) or whatever fair-trade, Gluten-free local store you shop at.

1. BIBLE

First thing’s first. If you’re going to memorize the Scriptures, you’re going to need a Bible. Here’s an important rule here: Memorize the translation you use! Do not memorize everything in the NASB if you never read anything but the NIV. I would recommend you memorize in either the ESV or HCSB if you aren’t committed to a translation, but it’s up to you. I do not recommend you use the KJV (archaic language) or the NASB (though an excellent translation, the language can be a bit wooden in many cases which makes memorization harder).

2. NOTECARDS

For this method of Scripture memorization, you’re going to need 3×5 notecards (not bigger, not smaller). 3×5, not 5×8.

3. NOTECARD DIVIDERS

Though not needed immediately, these are going to come in handy later (after you’ve become a walking Bible database). In phase 2, you’ll need 6-7. In phase 3, you’ll need 30.

4. Index Card Box

You’ll want to get a sturdy index card box. See mine below. Duct tape label is optional, but I believe duct tape makes literally everything better. I leave that between you and the Spirit.

Alternative Index Card Holder. These are good and portable. They don’t hold as many cards, however, and break easy. If you start with this, buy 5, not 1. It will tear up.

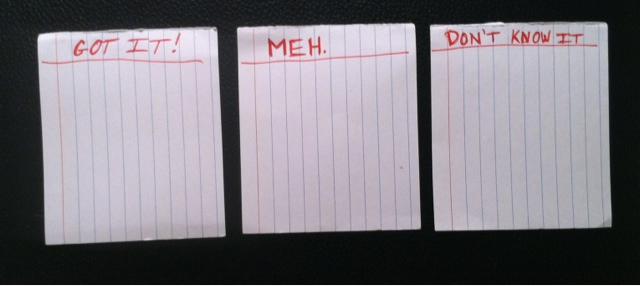

6. Main Section Dividers

Main section dividers are for your every day Scripture memory. These are the most important things to get. A typical start would be green in the front, yellow in the middle, and red at the back.

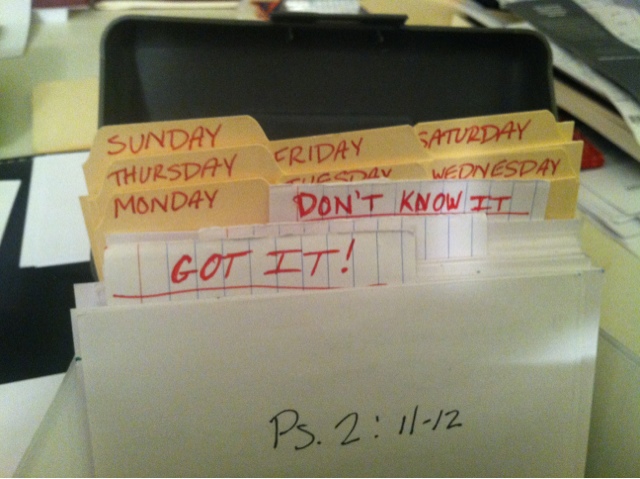

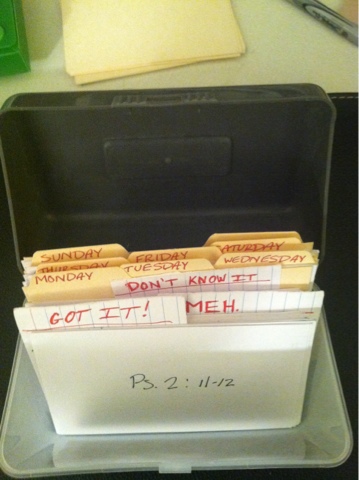

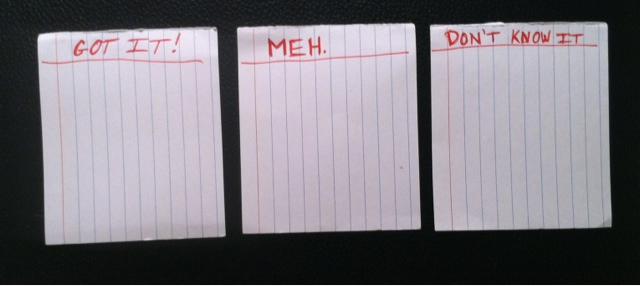

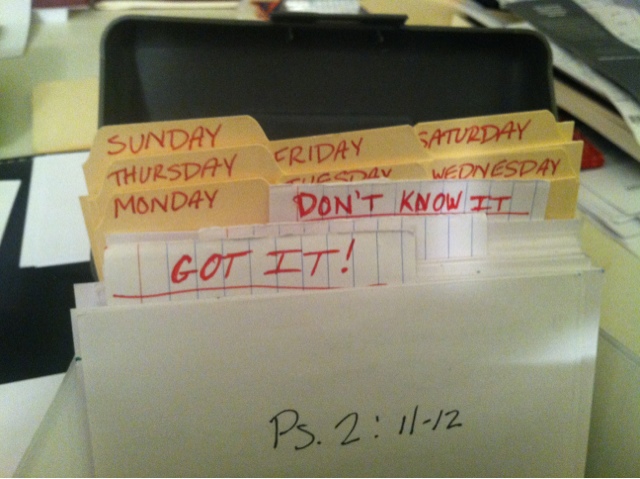

Alternative section dividers: These are my section dividers. Regardless, have 3 dividers which indicate 1) Verses you know word-perfect, 2) verses you are comfortable with but haven’t nailed yet or verses whose references you can’t remember, 3) Verses you don’t know at all or hardly know.

7. A Good Pen

Everyone needs a good pen for these. For my part, I use the Pilot Namiki Vanishing Point fountain pen (see below). This is, without a doubt, overkill. Whatever you choose, make sure it doesn’t bleed through the cards. Try to have a certain pen that you use with consistency. I generally discourage doing cards in different colors.

Using the Box for Scripture Memory

Phase 1:

Step 1: Dividers

Put your Main section dividers into the box. Cards go behind (or in front of — it’s up to you) these accordingly. Thee main dividers indicate the following:

- Green: These are verses you know. For a verse to be considered ‘known’ you must be able to recite it perfectly, word-for-word with no stumbling. you must know the exact reference. Reading the reference you can give the verse, reading the verse you can give the reference. You can say it fast, slow, whatever. You know it. However well you probably know John 3:16, that’s how well you want to know these. (This is my ‘Got it!’ tab)

- Yellow: These are verses you kinda know. You may even reference these verses in your daily life. You still mess up some of the words, forget the reference, or get things mixed up. Maybe you need the first word to get started. That’s ok! No big deal. Keep them behind this tab until you nail them. When you first start out, you will probably have the most verses here. (This is my ‘Meh.’ tab)

- Red: These are verses you don’t know. Some of them are verses you’ve just started to memorize. Some of them are verses you don’t know at all. When you do you time with the Lord and read a verse you want to memorize, write it on a card and stick it here. Even if you don’t get to it for weeks, this tab will hold it for you. This is where cards go when you first start to learn them and it’s where they stay until you are familiar with them.

Step 2: The Cards

Every Scripture Memory Card should be handwritten. Part of the memorization process is writing the cards, reading them in your own writing. If you have bad handwriting, slow down and take your time. I would insist that you write them, though. Trust me on this.

I don’t advise that you do more than 2-3 verses on a single card at a time when memorizing in isolation. I make exceptions for this. I memorized Ephesians in college using this method and I memorized 2 Cor. 4-6 two years ago using this method. When I did those, I left all the cards in order regardless of how well I knew them and each card was full. Except times like these, however, try not to do 4-5 verses. Practically, a bunch of cards that are super long can be discouraging because they take a long time to memorize. You may work weeks with little progress and quit. Instead, try shorter cards with only a verse or two and you’ll move very quickly! There are TONS of great verses to memorize before getting to chunks anyway. Let’s get started on those cards.

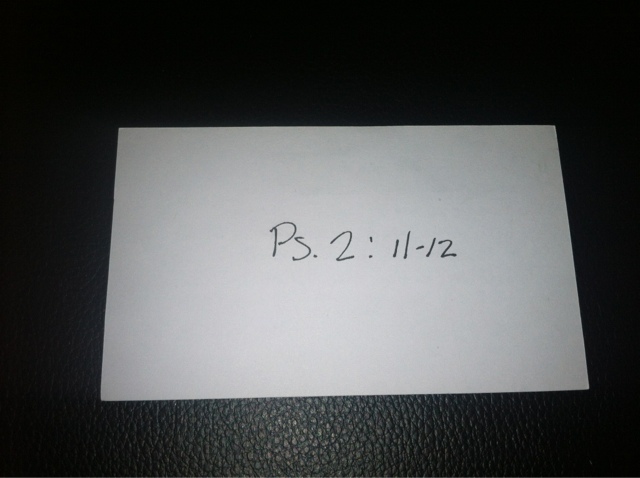

The front of the card should have a reference:

The back of the card should have the verse written out. Don’t cram the card.

Here’s a trick I learned from my friend Joe for cards that are really hard to learn. If you’re working on a single verse that you just can’t seem to make progress on, give it a shot. Write the first letter of every word and include the punctuation on the front of the card with the reference.That way, looking at the reference, you can work your way through the verse with what you know and familiarize yourself with the word order.

Romans 13:14 is where I had to do this. Those last few words leading into “to gratify its desires” always gave me trouble.

Step 3: The Verses

You need somewhere to start.You’ll want to start your box with 30-50 verses– don’t freak out! I know that’s a lot. Remember, most of them go behind the “Don’t Know’ and “Meh” (or yellow) tab. The first thing you need to do is figure out which verses you already know perfectly. John 3:16. Romans 5:8. Romans 3:23. Genesis 1:1. It doesn’t matter what they are. Write them down and put them behind the green tab. Starting with an empty green tab (Got It!) is discouraging. If you don’t know any, I’m so glad you’re starting! Odds are, however, you know at least a few. Get them in the green.

Next, find new verses to add.

Otherwise, Dr. Tim Beougher, Evangelism professor at Southern Seminary recommends

these verses.Step 4: The Box

Put the box together. Put in your divider tabs. Put in your notecards. I put my notecards in front of the tab. Why? At the back I put about 50-100 blank notecards to add more stuff. (Also, I suggest buying good notecards. Cheap ones bleed and wear out.)

What now? Memorize Scripture!

Every day is Scripture memory day. When you wake up, when you do your quiet time, before bed, during breakfast….you decide. But every day, find time to memorize scripture.

You can pick verses just for Evangelism, just for theology, just to fight sin, just for anything, really! One important note I will make is to not take things out of context. For example, memorizing Jeremiah 29:11 out of context may be unhelpful since you are not an Israeli exile or if you don’t understand God’s wonderful plan for you in Christ includes suffering for his name (Phil 1:27). Romans 13:14 is fine out of context. Not all verses are. Make sure you understand what you are memorizing!

There are 3 steps in your Scripture memory process:

- Go through every verse behind the green tab. It’s so incredibly easy to lose the verses you ‘know’. Don’t believe me? Did you ever learn a foreign language in high school? Do you know it now? Probably not. This is the same principle. You have to keep doing those verses! Every day, if you do nothing else (even if you don’t get to any new verses or ‘yellow tab’ verses) do these.

- If you have made it through green tab verses you know and have time, try to make it through your yellow tab verses. Don’t feel the burden to do all of them. That’s great if you have time, but even better is quality time with 4-5 of them. Do these until you can move them to the green tab. No pressure!

- If you’ve run through all the green tab verses and moved many yellow tab verses to the green, grab 2 or 3 from the red tab and start new verses.

You will find it helpful in your Scripture memory time to pray through the verses. This has been the most important use of Scripture Memory for me. For more information on praying Scripture, go here.

Also, meditation on the verses is key. Here is what you need to know about meditation.

John Piper has a helpful sermon on this.

For a practical guide to meditation, go here.

You may struggle with legalism on these. DON’T! Scripture Memory is a tool. It is commanded and it is an encouragement, but it does not and will never give you right standing before God. Don’t trust in how many days in a row you did Scripture memory for your self worth. Donald Whitney, one of the world’s leading authorities on spiritual disciplines, has written a helpful article on resisting legalism in spiritual disciplines.

Read it here.Phase 2:

How can there be more? Well there is! The good news about this Scripture Memory box is that it works. In fact, I have never met anyone EVER for whom this did not work. I doubted it and refused to do it for over a year. Then, struggling in my stubborn way, I switched to this and all of a sudden I was zooming through verses!

So what do you do when you have 50 verses behind the green tab, 40 behind the yellow tab, and 40 behind the red tab (Trust me– this will happen)? MORE TABS! This is where the 7 dividers come in handy.

Adding New Tabs

Once you have 30-40 cards memorized, the green tab can become burdensome to go through. Add 6-7 tabs (Some folks exclude Sunday), one for each day of the week. Once a card has been in the ‘green tab’ for a month or so, move it behind a ‘day tab’. Then, when you do your Scripture Memory time every day, do what is behind the green tab and add the ones assigned to that day. Try to keep the day tabs even so you don’t have 10 on Monday an 2 on Thursday. Even them out. This way you see every verse once a week.

Phase 3:

Adding Even More Tabs!

I don’t have a picture of phase 3. I haven’t gotten to that point yet, but I know plenty of folks who have. One friend of mine has multiple boxes, because this method has been so effective.

In Phase 3, keep your ‘day tabs’ and add tabs numbered 1 to 30. Yes, thta’s a tab for every day of the month. At this point, Scripture Memory time becomes ‘green tab’, ‘day tab’, and ‘day of the month tab’. Surprisingly, it doesn’t take that much more time. This will come once you have hundreds of verses. Don’t start the ‘day of the month’ tabs until you have 150 or more tabs behind your ‘day tabs’. I promise you, however, that if you stick to this you will get there within 2 years. Because of my switch to ‘large chunk’ memorization, my individual verse box memorizing slowed significantly. Stick to it, and you’ll know hundreds soon enough.

Conclusion

Remember, this isn’t the Holiness Olympics. You aren’t gaining right standing with God by memorizing Scripture. You are, however, equipping yourself to recite the Scripture when you are discouraged. You are equipping yourself to use these verses in Evangelism. You are equipping yourself to have a biblical theology. You are equipping yourself to know God more truly according to how he has revealed himself.

What are you waiting for?

Start memorizing!